Backstage footage of musicians in their natural habitat, away from the groping public, is often quite telling, even inspiring. Sometimes musicians you’d never expect to see sharing a stage are caught yukking it up in the wings. Ah, the glorious bonds of music know no bounds! In the above clip, videotaped backstage in Ocean City, Maryland, Dion and Marty Balin share a moment over a hair that fell into a third man’s beer. I’m not sure this tops the legendary footage of Bob Dylan and Lou Reed backstage in 1985, discussing the art of recording their music as it was meant to sound, but it comes close.

Will Your Mystery Date Be a Dream or a Dud?

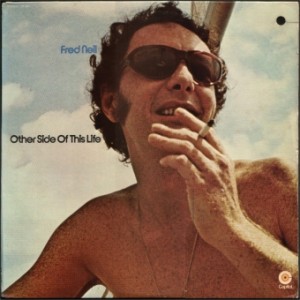

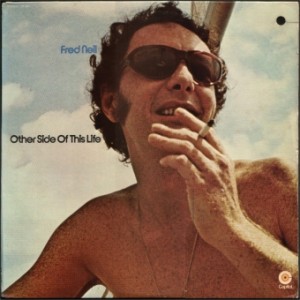

Well, our latest Mystery Date sure did have a deep voice, didn’t he, like he was singing from beneath the sea? The song was “You Don’t Have to Be a Baby to Cry,” performed by Fred Neil, who is thought of by pipe-tamping music lovers as a “Bleeker Street folkie” and who most of us young rock nerds learned after the fact was actually the author of lauded songwriter Harry Nilsson‘s biggest hit record, “Everybody’s Talkin’,” the theme to Midnight Cowboy. This number is from a collection of sides he cut from 1957-1961.

I didn’t learn until today that he was a Brill Building songwriter at this point, having written Roy Orbison‘s “Candy Man” among other songs for Orbison and Buddy Holly. Funny the stuff we learn along the way.

In my mid-20s, after learning a little bit about who Neil was, I would also forever associate him with one of the only Tim Buckley song I’ve been known to identify and enjoy, “Dolphins.” That’s one of those songs I believe a lof of Serious, Young, Genre-Spanning Artists have tackled. Here’s Buckley performing it on English TV, which I can only hope will inspire our recently dormant friend Happiness Stan to chime in with a story relating this song to one of his old girlfriends. I’m also hopeful that the likes of the Hall’s Deep Thinkers and Relative Folk-Bluesologists—dr john, mwall, dbuskirk, and even The Great 48 via his ’60s folk-scene bred wife—step forth with some insights into this artist and suggestions for songs to investigate that are as interesting as the 2 I know.

Neil was serious about these dolphins. Sometime in the early ’70s, the already reclusive Cleveland-born, St. Petersburg, FL-raised songwriter would turn his attention to preserving dolphins. The mind reels at what kind of music they made together?

Let’s review the ground rules here. The Mystery Date song is not necessarily something I believe to be good. So feel free to rip it or praise it. Rather the song is something of interest due to the artist, influences, time period… Your job is to decipher as much as you can about the artist without research. Who do you think it is? Or, Who do you think it sounds like? When do you think it was recorded? Etc…

If you know who it is, don’t spoil it for the rest. Anyone who knows it can play the “mockcarr option.” (And I’ve got a hunch at least one of you know this one.) This option is for those of you who just can’t hold your tongue and must let everyone know just how in-the-know you are by calling it. So if you know who it is and want everyone else to know that you know, email Mr. Moderator at mrmoderator [at] rocktownhall [dot] com. If correct we will post how brilliant you are in the Comments section.

The real test of strength though is to guess as close as possible without knowing. Ready, steady, go!

[audio:https://www.rocktownhall.com/blogs/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/Mystery-Date-062612.mp3|titles=Mystery Date 062612]

Steve Wynn & The Miracle 3 at the North Star Bar

I had intended to write this review in the wee hours of Sunday morning, while the post-gig metal machine music tinnitus was subsiding, while the deep satisfaction of seeing veteran bands do their thing was warming my already stoked heart (a heart that had, earlier in the day, seen veteran Man of the [Baseball] People Jim Thome smash a record-breaking walk-off home run), while conversations with the many Townspeople and other old music-scene colleagues were still fresh in mind. Instead I took some Tylenol PM, jotted down a few notes, and allowed myself to crash in preparation for Sunday’s day-long engagement party for my brother and his equally young-at-heart fiancee.

Freeda bassist!

That was the underlying message I took out of Saturday night’s show at Philadelphia’s North Star Bar, featuring The Fleshtones and Steve Wynn & The Miracle 3.

I love the bass guitar. Forty years after first wanting to be a guitar player I wish I’d chosen to be a bassist. No musician brings the “secret sauce” more effectively than a bassist. Except for a couple of freaky fusion bassists who don’t really count, bassists inherently start from a position of servitude. Like the ideal servant, however, the great bassists quietly lead from within, “powering up” the rhythm section, even saving the rest of a band from its worst impulses or limitations. A bassist can hunker down and drive a rhythm. A bassist can lay out on a key beat and imply some cool feeling that may not otherwise be evident in a song. A bassist can swoop high on the fretboard, playing “above the rim” while still holding down the lowest, least-obtrusive frequencies in a mix.

Freeda bassist!

The electric bass took off in the mid-’60s, when technology first allowed the instrument to be felt and heard. Motown’s James Jamerson was ready for the change. Stax/Volt house bassist Donald “Duck” Dunn caused no waves as a free bassist but relished his freedom nevertheless. Time had come for James Brown’s bassists to become movers and shakers in the free world. The Wrecking Crew’s Carol Kaye came a long way, baby. British Invasion bassists like John Entwistle and Paul McCartney set freedom marching across the globe. By the late-’60s bassists were regularly threatening to outshine the guitarists in their bands. Even people who don’t like the Grateful Dead, for instance, find merit in Phil Lesh‘s loping, melodic style. Lord knows I did the one time I saw the Dead in concert and had to sit through 3 hours of out-of-tune singing; lazy, noodling guitar runs; and unbathed, braless hippie chicks in threadbare t-shirts and long, floral skirts. Only Lesh and the mild pleasures of the swaying hippie chicks held my attention and kept me from reeling off into a bad trip, man. I am forever grateful to Phil Lesh for his prominent part in the mix that night in Chicago.

McCartney was up there with Jamerson as the freest of bassists: fluid, inventive, throbbing, you name it. They may have been the first two bass players of the rock era to receive the coveted All-Access Pass on their instrument. The All-Access Pass would later be used to infiltrate the deepest reaches of referential rock ‘n roll recordings by Bruce Thomas through his work with Elvis Costello & The Attractions. Just think of the half dozen mediocre Costello songs made worthwhile by the bassist.

Freeda bassist!

Do the math. New York rock ‘n roll primitives The Fleshtones have been in existence since 1976! Although I knew they dated back to the late-’70s and Marty Thau‘s old Red Star Records label, I didn’t have them pegged back quite so far as 1976 and the legendary New York punk scene of CBGBs, Max’s Kansas City, etc. To me they were pioneers of the second wave of garage rock that would blossom in ’80s underground rock circles. When I first saw the band at a small club in Chicago in 1981 or ’82, it was the closest I would get to stumbling across an actual Yardbirds- or Animals-inspired American ’60s band off the Nuggets compilation. They were sweaty, in-my-face exciting that night as singer Peter Zaremba swiveled his hips and swung his young Mick Jagger-style forelock over the crowd. Skinny guitarist Keith Streng rode his twangy chords and guitar riffs for all they were worth. He wore a turtleneck under a wide-collared shirt with a medallion to boot! Drummer Bill Milhizer and founding bassist Marek Pakulski laid it all out, implying nothing, avoiding anything remotely tasteful or subtle in their rhythms. Townsman Slim Jade wrote about our youthful attempts at defining ourselves through rock ‘n roll styles the other day. The Fleshtones really spoke to my initial efforts at becoming a new version of myself freshman year in a city far from home. My friend and I managed to get backstage after the show. We partied with the band. They seemed much cooler than us, but they were incredibly approachable. Shoot! Maybe, I thought, it wasn’t that far of a stretch to get a few notches cooler.

I saw The Fleshtones another 4 or 5 times through the ’80s, then lost touch with their activities. They were always a guiding light for me and my friends and our own band. It was always cool to know they were keeping things going as my friends and I kept our humble vision alive. Rock ‘n roll offers so many opportunities for community. That’s not to be missed or overlooked, no matter how frustrating any number of larger scenes may be. In chatting with Peter Zaremba the other day it was clear he and his mates are keeping things in perspective, doing what can and what needs to be done. Playing their patented brand of Super Rock. Taking it to The People in small clubs as they have always done.

The Fleshtones play Philadelphia’s North Star Bar this Saturday, June 23, with Steve Wynn and Miracle 3 (also interviewed here in the Halls of Rock), our old Philly music scene friend Palmyra Delran, and Sweden’s Stupidity. Tickets are available here.

Rock Town Hall: We interviewed Lenny Kaye just last year, but I did not know about your 2011 album with him, Brooklyn Sound Solution. The album sounds cool. How did he come to work with you?

Peter Zaremba: We’ve been admirers of Lenny’s since before Nuggets. He put together a compilation of Eddie Cochran stuff in the early ’70s that my friends and I thought was fantastic. When the Fleshtones finally got together, the first ‘cover’ we ever learned was “Nervous Breakdown” from that LP. Fast forward, we got word through mutual friend Phast Phreddie Patterson that Lenny really dug the band and would love to record with us—do some stuff that he couldn’t do with Patty. Of course we said yes!

RTH: Your “Super-Rock” sound and show can’t miss live. What does it take to capture it on record?

PZ: When you find that out, tell me. We’ll make a million bucks! Actually, it seems we look at our recordings a bit different than our “shows.” The show has the visual element, kinda like a “distraction” as used by a slight of hand artist or magician. You can get away with a lot when there’s so much going on. Now a record, you just sit and listen to. We’ve grown up listening to records and realize you have all sorts of opportunities to create whatever sounds you want. It’s a different thing entirely.

RTH: Did you fit in as you came about during the golden age of the CBGBs punk scene? In retrospect you seemed to be kind of “retro before your time.”

PZ: We really didn’t fit in, but I think we were more a taste of what was to come than a lot of what was considered “cool” at CBGBs at the time. However, we did fit in with the Blondie bunch, and oddly enough Suicide recognized us for what we were—distilled rock and roll, just like they were. The Johnny Rotten poses got old—quick.

RTH: Did that matter to your peers, critics, the scene?

PZ: Except for what I just said, I guess it did matter. We are pretty much written out of the history of that era.

RTH: How did your old MTV gig come about, as host of The Cutting Edge? How open was the network to your style and vision?

PZ: We were signed to IRS Records, who produced the show for MTV. We had appeared on the show already a few times and when the host decided to go to Fiji on an art grant (who wouldn’t!?!), they offered me the job. I took it. At first MTV didn’t care what we did, but when we became the highest rated “special” on the network, they really changed their minds! They wanted their hour back, and then tried to copy our formula with 120 Minutes. People are forever telling me how much they loved my show 120 Minutes! Anyway, we were the orphans of the network, even with our high ratings. I never get any acknowledgment from MTV, or invited to any of their anniversaries or events. It’s as if we never existed.

RTH: Have you ever done another solo record or offshoot record beside your old Love Delegation album? How did that come about?

PZ: No, The TWO Love Delegation LPs were enough to cure me, although I wouldn’t mind doing some sort of solo LP that would be 100% different from what we do in the Fleshtones. That takes money! How did the Love Delegation come about? Are we writing a book here? Lets just say that the Fleshtones were between labels at the time, we were in the middle of the Pyramid Club scene, with all of that incredible talent, energy and crazy ideas, and I had piles of material that I wanted to use.

RTH: The Fleshtones have endured for more than 35 years, doing your own thing, your own way. Is there an old record or artist the band taps into to help keep the faith?

PZ: At this point, we are our own inspiration, and for others!

RTH: Have you ever been tempted to veer off into some new direction? Have you or Keith had to put aside any stylistic urges for the good of the band? For instance, is there a closet prog rocker in the band?

PZ: I hope there isn’t a closet prog rocker in the band. You’d think I’d know if there was by now, but you never know! We love basic rock and roll. There’s a lot you can do with that. No big changes.

The “money shot,” that big payoff moment… In the first installment of our Money Shot series we examined rock’s most influential vocal money shot moments. While we await the return of Townsman tonyola before exploring mellotron money shot moments, let’s turn our attention to the bass guitar.

Putting aside outright bass solos (sorry, John Entwistle on “My Generation”), what brief, shining moments in a song are brought to new heights by something as simple as a bass lick. I will suggest John Paul Jones‘ measure-long bass fill following the first chorus in “Good Times Bad Times,” heard at the 54-second mark of the following clip.

Imagine how many kids bought a bass guitar in hopes of learning that lick. Now what’s your bass guitar money shot?